EVO, MAMA COCA’S MYOPIC SOLDIER - BOLIVIA, 1993-2013

by Adriaan Bronkhorst. Amsterdam – La Paz

Without any respect for the first peoples of this world and their cultures with the longest histories, the last great nation to appear on the world scene, with the shortest history of them all, imposed on the mere basis of ideological preferences the prohibition of the plants of their gods, that are intricately interwoven with their culture and physical and spiritual well-being. Their future use of these plants was forbidden. A pure act of ethnocide. The historical testimony of the nature peoples about the properties and advantages of these forbidden plants was henceforth refused to mankind, relegated to the historical taboo, an act of planned falsification of history. The UN, charged by its Charter with the promotion of peace and security, quieted the people that may teach us about their millennial experience of living in peace with the earth. The end of territorial colonization that swept the world in the 1960’s was at once replaced by the Yankee colonization of the world population’s mind by the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.

The arrogance as embodied in the Single Convention was addressed by Mr. Ossio Sanjinés, interim president of Bolivia, in his letter of recommendation for Mauricio Mamani Pocoaca, the first drug pacifist nominated by the Drugs Peace Institute for the Nobel Peace Prize. (for copy of the letter see below). Mr. Sanjinés wrote: “The struggle to claim the benefits of the coca leaf, as well as all those crops that traditionally represented the culture of the Andean peoples, is and has been long and difficult, often due to the lack of knowledge of the public and others due to the misrepresentation of their applications. The truth is that the coca leaf should be the object of a great reflection on its intrinsic merits in the service of the Andean peoples and of humanity in general.” Ossio Sanjinés expressed the feelings of disbelief and anger of a nation that after centuries of Inquisition observed how the new United Nations had obliged to the white Anglo-Saxon protestants and their allies to destroy the spiritual life of the Andean peoples by outlawing coca, while simultaneously claiming to guarantee freedom of religion with the adoption of the International Bill of Human Rights.

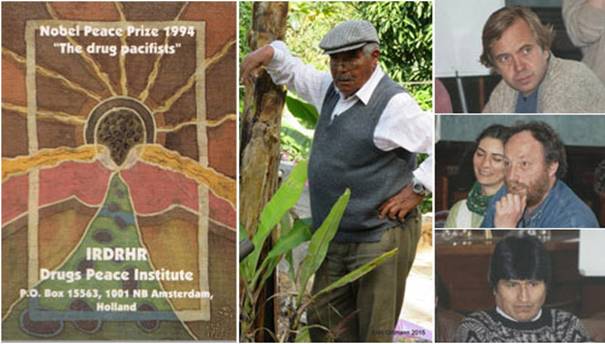

Flyer for the 1994 Nobel Peace Prize (NPP) “The Drug pacifists” and the first nominee

Mauricio Mamani Pocoaca

|

|

Nominees for the 1996 NPP : Ben Dronkers, John Marks and Evo Morales Ayma (Morales was also nominated in 1995)

|

Ossio Sanjinés was joined in his support of Mauricio Mamani by an overwhelming part of the Bolivian society and the DPI thereupon organised the 1995 nomination of Evo Morales, leader of the cocaleros (coca farmers) in the Andean region. With the help of the European green and left parties Morales also got nominated. Based on the realization that the war on drugs wrongly punishes all users of prohibited substances and that unity of action is required to free the users of all means of this criminal regime, the DPI promotes mutual cooperation. The whole exercise was therefore repeated in 1996 when cannabis' Ben Dronkers and the famous Merseyside clinics doctor, John Marks joined the ticket.

As an immediate result the substantial donation by Dronkers' Sensi Seeds to Marks and Morales allowed the latter to purchase a 4wheel drive and visit his electorate in the vast Chapare region to participate in the 1997 national elections and win his first 4 seats in the Chamber of Deputies. Upon his inauguration as president of Bolivia in 2006, he declared that he owed his political success to a significant degree to European cannabis movements and in particular to Ben Dronkers. The 4wheeldrive he received would therefore be exhibited in the entrance hall of the Museum in his honor in his birthplace Orinoca, as a lasting reminder of his gratitude.

Meanwhile, international awareness of the great value of psychoactive plants for the survival of traditional cultures had been demonstrated with the 1971 Vienna Convention on Psychotropic Substances which addresses, amongst others, psychedelic compounds like psilocybin and mescaline, naturally occurring in psilocybin mushrooms and the san pedro and peyote cacti. The new convention dropped the requirement of the Single Convention for the termination of the traditional ‘quasi-medical’ use of the plants under consideration. This time around the US agreed to “a consensus that it was not worth attempting to impose controls on biological substances from which psychotropic substances could be obtained” because “the American Indians in the United States and Mexico used peyote in religious rites, and the abuse of the substance was regarded as a sacrilege.” The Mexican delegate added that such a prohibition would conflict with the Mexican Constitution, which stipulates that all men were free to hold the religious beliefs of their choice and to practice the appropriate ceremonies or acts of devotion in places of worship or at home. Here it was officially admitted that the beneficial use of a substance is possible as the outcome of a social process of accompaniment and guidance.

Contrary to the coca leaf, chewed by Aymara and Quechua peoples in the Andes for whom abuse is as great a sacrilege, the Vienna Convention addressed substances of which the religious use, in this case peyote, is practiced by indigenous peoples in the US. The deciding argument for the turn-around, nowhere mentioned, is thought to be the fact that the US constitution too protects the traditional use of psychedelic substances under the right to freedom of religion so that, unlike plants as cannabis and coca that had no traditional use in that country, the traditional peyote use had to be accepted. For tactical reasons this argument, in plain contradiction with the drug control regime, was not advanced by the US who, instead, presented its agreement with this traditional use in the 1971 Convention as a concession to the international community. This approach allowed it to repeat the turn-around in the opposite direction when, in 2009, Bolivia sought to remove the provision that “coca leaf chewing must be abolished” from the Single convention in order to reconcile its international treaty obligations with its 2009 Constitution, which obliges upholding the coca leaf as part of Bolivia’s cultural patrimony. The US convened a group of “friends of the convention” to rally against what was presented as undermining the integrity of the treaty and in this way succeeded in thwarting Bolivia’s attempt to amend the Single convention. A second attempt by Bolivia, leaving the Convention and re-entering with a reservation about traditional coca-chewing, was successful in 2013. Although the US had recruited the whole G8 to object, the final number of objections fell far short of the 62 (one-third of the 184 convention members) required to invalidate the reservation. The friends of ethnocide were defeated by Bolivian president Evo Morales Ayma in his quest for redress for their 500-year long crushing of the Andean people’s cultures.

This remarkable victory of the Bolivian president confirmed however the disturbing fact that all the superpowers still stood by the ethnocidal drug control policy of 1961, apparently unhindered by their obligations under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Transnational Institute’s Martin Jelsma speaks of “the inquisitorial nature” of the UN-attitude, reminding us of the colonial history Ossio Sanjinés, Evo Morales and their South-American colleagues see perpetuated by the drugs prohibition. It shows that despite half a century of awareness building by the indigenous peoples, the UN Charter and Treaties on individual and collective rights must give way once the world’s drugs regime comes into play and ethnocide of traditional cultures by the contracting parties to the drug control conventions is considered as a logical end.

Sadly enough, Evo fell back on his own prohibitionist position. He obtained a deserved reservation for the traditional use of coca leave chewing for his country’s indigenous peoples but increased the penalties for the use of other substances, starting with cocaine and marihuana. To appease his prohibitionist detractors he had always stuck with his slogan ‘Coca no es cocaina’ but in the end he forgot that both users of coca and cocaine are humans, entitled to human rights. Fueled by 500 years of subjugation and humiliation, his hatred against the former colonizers would justify a punishment that, in his own words, might last another 500 years. The irony of Morales’ ‘new’ prohibition policy is that, under the guise of a more representative society, he sort of embedded it in the new constitutional organization of Bolivia, nowadays called a Plurinational State. In this State, different Nations -cultural or ethnic groups- appear to have different rights. But those rights are not always defined according to the wishes and needs of the different nations but of the Aymara ruler and his desire for punishment, just as prohibition has always done.

Imagine that Nelson Mandela, instead of arguing to abolish the apartheid in South Africa, had strategically shifted his position and argued to make exceptions within the apartheid? Mandela making an exception for the Xhosa and siding with the apartheid regime in exchange? Inconceivable and a strange and untenable position to adopt! In South-African terminology Evo embraced the hated Bantustans, the pseudo-national homelands for the South African black inhabitants. Evo proves us right: neither exceptions nor reforms will do, only the end of prohibition, otherwise the corruption of power will continue prohibition, for others, with consumption preferences different from those of the rulers, too short-sighted to recognize the advantages of what does not fit into their own tradition.

See also: Dr. Julian Buchanan, Breaking Free From Prohibition: A Human Rights Approach to Successful Drug Reform |

English version

La Paz, Bolivia, July 14th, 1993.

Señor

Adrian Bronkhorst

IRDRHR i.o.

Casilla Posta 1 15563 Casilla Posta 1 15563

NL-10 0 NB Amsterdan

Holanda

Dear Mr.Bronkhorst:

The struggle to claim the benefits of the coca leaf, as well as of all those crops that traditionally represented the culture of the Andean peoples, is and has been long and difficult, often due to public ignorance and others due to misrepresentation of their applications. The truth is that the coca leaf should be the object of greater reflection on its intrinsic merits in the service of the Andean peoples and of humanity in general.

In this struggle to reestablish, in its proper proportion, the cultivation of the coca leaf as a patrimony of Andean cultures, no one has carried out greater scientific research than the anthropologist Mauricio Mamani Pocoaca, current National Deputy, in authentic representation of the Aymara nation to which it belongs and fiercely defends. ·

It is in light of this background that I support the nomination of Mr. Mauricio Mamani Pocoaca for the 1994 Nobel Peace Prize.

With this gratifying reason, I reiterate to you, the expressions of my highest consideration.

Dr. Luis Ossio Sanjinés PRESIDENTE CONSTITUCIONAL INTERINO DE BOLIVIA

PRESIDENTE DEL CONSEJO NACIONAL DE CIENCIA Y TECNOLOGIA |