Ritual re-enactment of the encounter with the world of the divine

Zuni creation mythology recounts how, after having emerged from the earth, the people went looking for the Middle, the place where they would settle. Fording a river on the way, the first women to enter the water saw their children turn into frogs and water snakes. Horrified they dropped them and the creatures swam away.

| |

"The bereaved mothers mourned for their lost children, so the Twin

Heroes were sent to see what bad become of them. They found them in a house beneath the surface of

Whispering Waters .... transformed into Katcinas [impersonated spirits], beautiful with valuable

beads and feathers and rich clothing. Here they spent their days singing and dancing in untroubled joyousness.

The Twin Heroes reported what they had seen, and further decreed that thereafter the dead should come to this

place to join the lost children." [Bunzel, Ruth, l."Introduction to Zuni Ceremonialism," from the Forty-seventh Annual Report of the Bureau of Americam Ethnology, 1929-1930, Smithsonian

Institution, Washington D.C. |

|

After having found the Middle, on top of Corn Mountain, problems arose:

| |

".... they questioned one another: "How shall we enjoy ourselves? Now the men are greatly increasing in number and the women are greatly increasing in number. It is not yet clear with what pleasures we shall pass our time." [Bunzel, ibid] |

|

Unable to find ansers to the problem at hand they sent their prayers to the Whispering Waters, where the Divine Ones decided to send them the Kachinas of the Lost Children to dance for them. The people enjoyed the dancing but each time the Kachinas came, they took someone with them when they went (someone died).

| |

"Then these (the Kachinas) said, .... If we keep on coming it will not be right." Thus they said. "You will look at us well. We do not always look like this." Thus they said. Then the two set down their face mask and their helmet mask. The people looked at them (the masks). As they looked at them they said: "You will look at them well so that you can copy them. You will make them and give them life. When you dance with them we shall come and stand before you. If we do thus perhaps it will be all right, because if we take someone with us when we come it is not right. Thus they said to one another. Then they made them. When they brought to life the chin mask and the helmet mask, the people of the village danced in them. They made them right, and the people of the village were happy. No one died. Thus they live. When they danced thus no one died. Thus they lived." [Bunzel, ibid] |

|

In the above quoted parts of the Zuni creation myth we are told how on the way to the Middle, their present state of civilization, the people lost their first children when crossing the stream.These children symbolize the innocence lost on the way to maturity and responsability. As their society increased the people lost the joy of living experienced earlier, before they had crossed the river and the Whispering Waters, also called the Whispering Spring. That spot, home to the spirits of their children and to the Divine Ones, the Twin Heroes, reminds us of the realm beyond the waters at the end of the world where the gods of the Mesopotamian pantheon fled to, and remained forever, after the Flood had covered the entire earth. In the two myths water divides the realm of the divine and the eternal life of the spirits from the world of humans and inevitable death.

| |

|

|

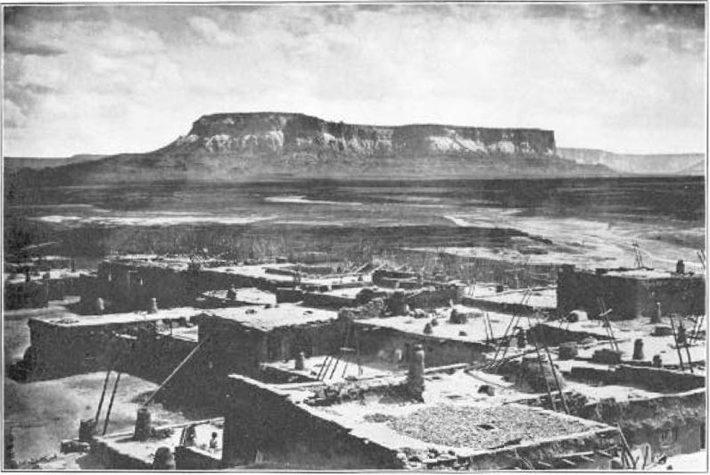

| Corn Mountain with the Zuni pueblo in the foreground. (Photo Buureau of American Ethnology, 1908-1909) |

The life found by the peyote eating Huichols after having met their personal gods in ecstatic trance on top of the mountain, has become unattainable for the Zuni populace, barred from the consumption of A'neglakya and its life giving properties. When the Kachinas would visit them on Corn Mountain they would bring deatn instead, so the myth goes. It is at this point that the subterfuge of the divine masks is introduced, the sacred fetiches used to keep the world of the death-bringing-spirit at bay while allowing the people to imagine these spirits' presence in night long frenetic dancing. "When they danced thus no one died. Thus they lived."

The myth exhorts the interlocutor to believe that the messengers from the world of the spirit brought death while through the dance that imitated that divine presence, they would get life.

The interlocutor addressed by the myth was in the first place the unhappy tribesman on top of Corn Mountain, bereaved of the encounter with his personal god and the life giving properties erstwhile bestowed in that encounter. The existential anguish that now surfaced in the absence of the direct encounter with his personal god had made this man - and the rest of the tribe as well - unable to enjoy life. Through the fake claim about the enjoyment of the dance which stopped people from dying and made them live, the Talk of the Katchina was used to deflect attention away from the loss of existential happiness, the loss of the children, and instill faith in the power of a surrogate religious ritual performance.

For those questioning the truth of the story the priests added a pedagogic ending:

| |

"Some young woman was watching the dance with her little boy. They danced. It was all over.

A few days later the children were playing outdoors. A young man went by where the children were playing. The little boy said, "See that young man going by there? The other night he was a Kachina maiden. Perhaps the masked gods do not really come." Thus he said. The children heard him. When they came to their houses, they told their elders. "Perhaps the masked gods do not really come." Thus they said. "Who said so?" "K?ai'yuani says so." Thus they said. "Keep quiet! Don't do that. They will punish you." Thus they said to them. Their fathers told one another. They talked only of that.

In the kivas (communal gathering places) they worked on their masks. They made some dangerous monsters. When they were ready they came. They went around searching. In all the village they could not find him. Meanwhile his parents were hiding him way back in the dust in the fourth inner room. They just brought him food. When they (the parents) did not see him they sent word to the village of the Kachinas. When their message came to the village of the Kachinas they arose. The

sayalhia and white temtemci and the koyemci and all the Kachinas came hither. They went about searching. They called into all the kivas. When they had been to all of them and found no one there they came to his house. They called in. "He's not here. He has gone far away." The koyemci came down. "We can't find him," they said. When they had said this the sayalhia stood on four cross marks (on the roof). Two of them stood facing the east, the other two stood facing the west. They turned around. When they had made a complete circuit they called, "Bu----ix!" The earth shook. The second time they turned about. When they had made a complete circuit, "Bu----ix!" they said. The walls of the house cracked. They turned around the third time. When they bad made a complete circuit, "Bu----ix!" they said. (80) The house cracked nearly to the ground. The fourth time they turned around. When they had made a complete circuit, "Bu----ix! " they said. The walls cracked all the way down to the ground; there in the fourth room be was sitting. The koyemci said, "Look in there, our little friend is sitting within!" Thus they said. They pulled him out. The Kachinas came. They struck him. When they were finished the white tomtemci walked around angrily. "Hoo--tem-tem-ci tem-tem-ci hoo--!" "Grandfather hurry! Hit him hard! We want to go!" Thus said the koyemci. Temtemci was angry. He was running around angrily. After a while he went over to where the boy was standing, He seized his forelock. Huk^we! He cut him. He cut his head off at the neck and threw it up. It fell. He picked it up and again threw it up. It fell. He picked it up and again threw it up. It fell. Again he threw it up. It fell. Then the koyemci used it as a kick stick. They came to the village of the katcinas. Near by on an ant hill they set it down. Then they went in.

Meanwhile at Corn Mountain they buried K?aiyu?ani's headless body. By doing thus they made the Kachina society valuable. Therefore, to any little boy who is initiated into the Kachina society the Kachina chief tells this story. Whoever forgets and talks of this will be punished. Therefore these words are not to be told. You will be mindful of it." [Bunzel, ibid]

|

|

The lost children pitied the loneliness of their people and came often to dance for them in their plazas and in

houses prepared for their use. But after each visit they took someone with them (i. e., someone died).

Therefore they decided no longer to come in person. So they instructed their people to copy their costume and

headdresses and imitate their dances. Then they would be with them in spirit.

|

In this story, written at the occasion of the Ugarit king’s enthronement, sovereignty had been given to a ruler and society would have to make do with the symbolic ritual that invested the king with the sovereignty in representation of all his people. Wyatt explains: “This ritual process was in one, psychological, respect the whole purpose of the liturgy, because the identification of men with the gods, even if only through their representative, the king, was an escape from the alienation that marks the human condition.” (Idem, p 57 [pdf 16R]) [20210902_Letter for L]

pdf 11

the effects of psychoactive substances appear to be similar to those of breathing in chant and recitation .....

The inhaling and exhaling that accompanies the gigantic opera or breathing exercise of a Soma ritual is one of the features that helps explain how a psychoactive substance can become a ritual. Frits Staal, How a Psychoactive Substance becomes a Ritual, pdf 11 |